Background

Incidents of police killing of civilians, corruption, and misconduct in recent years have led to greater for calls and actions related to police reform. Various measures have been proposed to reduce disparities in policing activity (e.g., deprioritizing proactive traffic enforcement), reduce unconstitutional policing actions (e.g., emphasizing de-escalation), and improve accountability of officers and law enforcement organizations (e.g., implementing early warning systems). However, advocates for policing reform have argued that law enforcement unions present a crucial barrier to implementing many of these measures. Through collective bargaining agreements, unions have been shown to exacerbate problematic law enforcement behaviors by undermining discipline and accountability (Cunningham et al., 2020, 2021; Dharmarpala et al., 2019; Harris & Sweeney, 2019; Keenan & Walker, 2005; McKesson et al., 2016; Rad, 2018; Rushin, 2016). Nevertheless, empirical evidence on the impact of police unions is far from clear. Important gaps remain in our knowledge about union contracts, their variability, and their role in affecting various policing outcomes.

Research conducted by the National Policing Institute sought to understand the role of unions in shaping accountability and officer health and wellness mechanisms. By examining detailed information from police union contracts associated with 82 large police agencies in the United States, we sought to illuminate the differences in the types and extent of protection union contracts provide to officers. We further explored agency characteristics that may explain the similarities and differences in union contracts. Utilizing the variability in contract protection against misconduct complaints, we then investigated the effect of union protection on outcomes such as violent misconduct and legislative efforts at policing reform. In this post, we present part of the findings.

Data & Methodology

We analyzed union contracts from 82 of the largest police agencies in the U.S., initially obtained from the open-source database compiled by Campaign Zero (checkthepolice.org). Expanding from the original coding categories used by Campaign Zero, we developed a 90-item coding instrument that identified major areas in the contracts. We grouped these 90 items into seven categories including:

- Officer protections prior and during complaint investigation

- Officer protection during complaint investigation

- Officer protection post-complaint investigation

- Limitation on community oversight

- Internal grievance

- Benefit protection

- Provisions for mental and physical wellness

These seven categories were further divided into 17 scales based on the categories addressed in contract clauses as shown in Table 1.

| Protection | Categories | Scales |

|---|---|---|

| Complaint Protection | Officer protection prior and during complaint investigation | 1) Complaint limitation |

| 2) Officer access to complaint information | ||

| 3) Officer rights during misconduct investigations | ||

| 4) Interview protections | ||

| Officer protection post-complaint investigation | 5) Discipline limitations | |

| 6) Misconduct records | ||

| 7) Criminal cases | ||

| 8) Department/city liability | ||

| Limitations on community oversight | 9) Public access to information | |

| 10) Civilian oversight | ||

| Internal grievance | 11) Internal grievance | |

| Benefit and Wellness Protection | Benefit protection | 12) Working hours |

| 13) Incentive pay | ||

| 14) Promotions | ||

| Provisions for mental and physical wellness | 15) Injuries | |

| 16) Mental health assistance | ||

| 17) Physical fitness requirements |

To examine variability, K-means clustering analysis was conducted to categorize agencies into nonoverlapping groups based on contract provisions. Cross-cluster comparisons were conducted to examine differences between agency clusters.

Next, to understand the mechanisms that affect contract protection, coded union contract data were merged with a variety of data sources on agency characteristics including crime rates, arrest rates, officer representation of minority populations, fatal encounters at baseline, use of community policing, mayor’s political affiliation when signing the contract, and state police officer bill of rights (PBOR).

To explore the antecedents and impact of contract protection, regression models with regional fixed effect and clustered regional standard error were conducted. We focused on two aspects of protection, overall complaint protection and benefit and wellness protection (Table 1). These will be presented in the next post.

Finally, to evaluate the impact of union contracts on police excessive use of force, we performed analyses on police killings of unarmed civilians between 2015 and 2021 sourced from Campaign Zero using the same set of covariates plus contract complaint protection. For the reform outcomes, logistic regressions were conducted on state legislation enacted after the murder of George Floyd on policing reform (coded dichotomously using data accessed January 2022 from National Conference of State Legislature), either pertaining to any substantive area of policing or on police use of force specifically. These results will also be presented in the next post.

Results

Clustering Analysis – Variability in union contracts

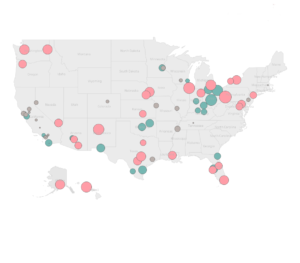

Figure 1 shows the geographic distribution of agencies assigned to each cluster.

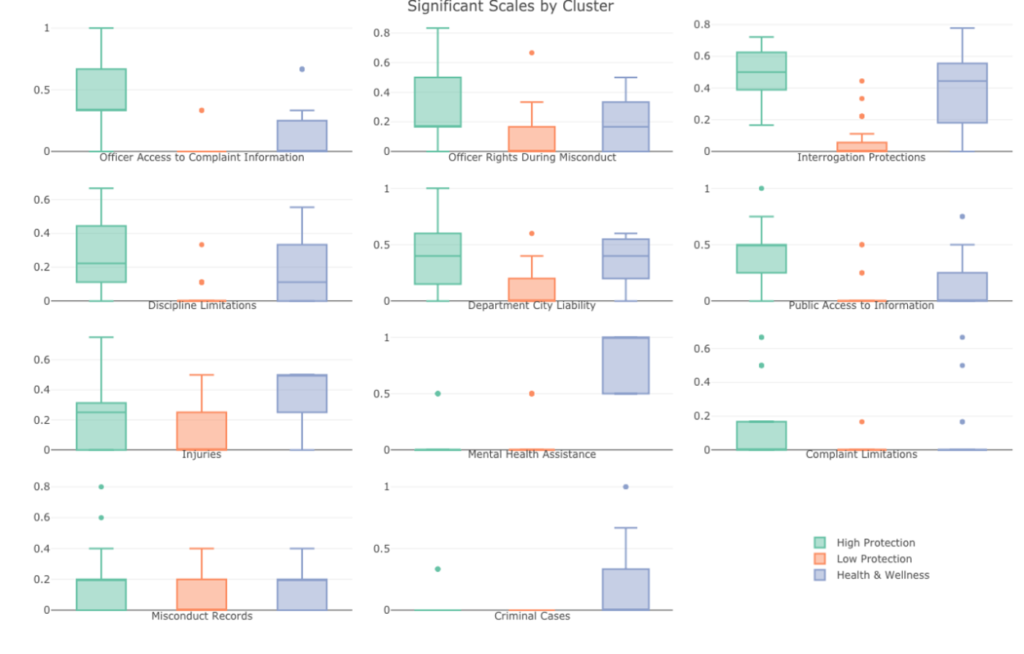

Higher Officer Protection Agencies – Union contracts from agencies in the Higher Protection Cluster (29 agencies) contained provisions offering the greatest protection for officers. Union contracts from agencies in these clusters tended to:

- Feature limitations on complaints such as time to file, anonymity, and investigation duration. For example, the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police contract stipulated that all complaints must be filed within 90 calendar days of the event, otherwise the complaint shall be classified as unfounded (Working Agreement Between the City of Pittsburg and the Fraternal Order of Police Fort Pitt Lodge No.1, 21 A2 (2010)).

- Be more likely to grant officers access to complaint information and offer greater protections during complaint investigation and interview. The Albuquerque Police Department contract allowed officers to consult with their union representative before being questioned and to have a union member present during any questioning (City of Albuquerque and Albuquerque Police Officers Association Collective Bargaining Agreement, Article 20.1.11 (2014)).

- Impose more limitations on discipline, expunge misconduct records after a period, and have limitations or policies on criminal charges against officers.

- Place more liability for officer actions on the agency. In the event of compensation or settlement these contracts tended to limit public access to information related to complaints and disciplinary actions against officers. The Omaha Police Department restricted the public disclosure of officer discipline (Agreement Between the City of Omaha, Nebraska and the Omaha Police Union Local No.101, Article 18A, I (2008)).

- Have more constraints on civilian oversight (e.g., limitation on information subject to release).

- Have lower levels of officer protections related to on the job injuries and mental health assistance.

Lower Officer Protection Agencies – The agencies in the Lower Protection cluster (30 agencies) had union contracts with the least amount of officer protection. This cluster contained more than a third of the sampled agencies. Contracts in this cluster were characterized by:

- Minimal protections for officers regarding citizen complaint investigations and interviews, disciplinary actions, and public access to complaint information.

- Lower levels of agency or city liability for officers’ misconduct.

- Injury and mental health assistance protections were less common.

Health and Wellness Protection Agencies – Agencies in the Health and Wellness Cluster (23 agencies) had a mix of provisions and scored in the middle on many indicators. Union contracts from agencies in these clusters tended to:

- Provide higher levels of protection regarding officer rights during misconduct investigations, limitations on discipline, misconduct record, criminal cases, and department or city liability.

- Were less restrictive on complaint submission, had less provisions for officers to access complaint information, and imposed fewer limitations on civilian oversight.

- Have less protection than the contracts in the Higher Protection Cluster on public access to complaint information.

Agencies in this cluster placed more emphasis on provisions covering mental health assistance and injuries. For example, the Cleveland Police Department provided temporary restricted duty assignments for individuals injured in the line of duty, and ensures that line of duty injuries do not interfere with salary or benefit accrual (Collective Bargaining Agreement Between the City of Cleveland and Cleveland Police Patrolmen’s Association (C.P.P.a) Non-civilian Personnel, Article XXI, 49, A & D (2013)).

Figure 2 visualized the 11 scales where the three contract clusters showed significant difference.

In the next post, we will describe the regression analyses of the antecedents and outcomes of the union contracts including predicting contract complaint protection, contract protection for benefit and wellness, police killings of unarmed civilians, and state legislative reform on policing.