An Evaluation on the Impact of Active Bystandership Training

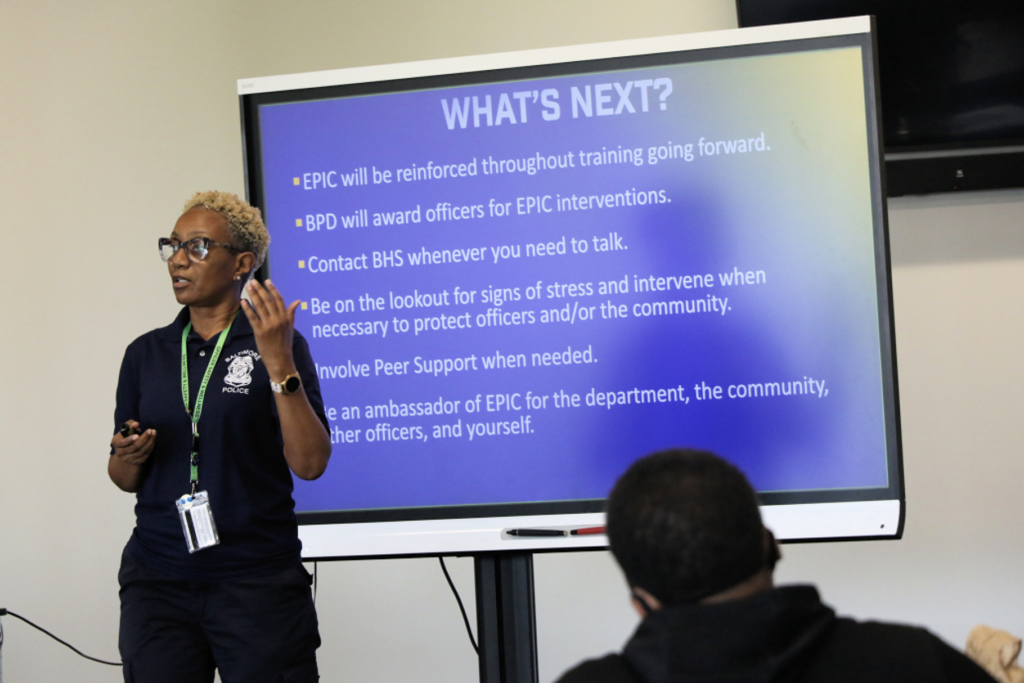

In this post, we present part of an ongoing evaluation of Active Bystandership (AB) training that has been conducted in the Baltimore Police Department (BPD) through the recently-launched Ethical Policing is Courageous (EPIC) program — an agency-level initiative designed to facilitate and empower officers to effectively intervene during potentially harmful situations. To evaluate the impact of EPIC training within the BPD, and to inform potential future AB training in other police departments, we conducted an officer survey immediately post-training which resulted in 1,753 responses. Overall, EPIC training was perceived positively by respondents. Respondents generally found the training to be useful and indicated that it would promote and facilitate ethical conduct. Respondents indicated somewhat less confidence in intervening with their supervisors compared to peers. Written comments indicated that officers wanted more AB training and more scenario-based training.

Background

A bystander is defined as a witness who is in a position to know what is happening and can take positive action (Staub, 2018); an active bystander is someone that recognizes when action is needed, decides to act, and consequently intervenes (Latané, 1970). It is believed that active bystandership can be a facilitated or encouraged behavior. In law enforcement, AB training is designed to enhance peer intervention and (1) prevent misconduct, (2) avoid mistakes, and (3) promote officer health and wellness.

The first known implementation of AB training by a law enforcement agency was in the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD), who initially created the EPIC program in partnership with researchers and community partners. The training was developed to teach officers peer intervention skills (Aronie & Lopez, 2017), promote an organizational culture of transparency by engaging the leadership staff, and normalize AB by establishing protections for officers who intervene (NOPD, n.d.). Most recently, building upon EPIC, the Innovative Policing Program at Georgetown University Law Center developed the Active Bystandership in Law Enforcement (ABLE) Project to provide police agencies with practical, scenario-based training in the principles of AB and strategies for effective peer intervention. The stated goals of ABLE training include:

|

|

Data & Methodology

A survey was designed to assess the following dimensions: perceptions about the training, application of the training to the job, willingness to address ethical challenges, confidence in the ability to intervene in a variety of situations, and an open-ended section to capture general comments about the use and quality of the training. The survey was disseminated to the officers after completing EPIC training. 2,029 participants completed EPIC training; 1,996 surveys were submitted (98.4% of the total trainees); 1,753 submissions (87.8% of survey responses; 86.4% of all training participants) provided useable data.

Results

Was the training likely to promote active bystandership and ethical behavior?

- More than 80% of the respondents indicated that they thought the training was likely to promote ethical conduct (81%).

- A large majority of respondents indicated a greater likelihood of intervening after completing the training (82%) and having confidence in their ability to intervene with peers (86%) and supervisors (79%).

- Most respondents were confident that fellow officers would support them in intervening (76%), but the percentage of respondents indicating they would receive support from a supervising officer was slightly lower (70%).

- As a result of training, most officers were thinking about the benefits of intervention to prevent misconduct (82%) and promote the health and safety of their coworkers (84%).

When would officers intervene?

Officers indicated willingness to intervene across a wide variety of scenarios, including: confronting fellow officers who had violated departmental policy, appeared to be making an unjustifiable search, or were demonstrating unusual behavior or moods. They were also likely to refer coworkers to behavioral health services. Agreement with these questions ranged from 73% to 84%. Officers were slightly less likely to report willingness to intervene with supervisors, but the difference was small (usually less than 10%).

How willing are officers to confront moral challenges?

Officers indicated a strong willingness to face moral or ethical challenges. Most respondents (70%) were willing to take on ethical challenges even if they might incur negative consequences, hold their ground on moral matters (85%), and think they acted morally even in conflicts with supervisors (80%). Two-thirds of respondents indicated that they were never or seldom swayed from acting morally by fear or other negative emotions (69%). 42% of respondents indicated that they would bring moral issues forward even if it put themselves or others in jeopardy.

How confident are officers in intervening?

Officers indicated considerable confidence in their ability to intervene in a wide variety of situations. They were most confident in responding to co-workers using excessive force (86%) and in peer-to-peer verbal altercations. There was slightly less confidence reported in responding to supervisors that show up for work hung over (66.7%).

What did we learn?

Officers generally perceived the training as useful and likely to promote ethical conduct. They consistently indicated that they felt more confident and willing to intervene because of the training. Respondents also indicated that they recognize the benefits of AB for the health and safety of their coworkers.

Officers indicated that there were more concerns with intervening with supervisors compared to peers. The strongly hierarchical nature of law enforcement agencies makes it understandable that people may find it challenging to intervene up the chain of command. It may be necessary to better emphasize, in-class and reinforced through future communications, the application of peer intervention in a way that is agnostic to rank. It is also likely that an organizational perception of willingness, and appropriateness, of intervening with supervisors may take considerable time to develop. Longer-term follow-up on this issue is warranted.

Open-ended respondents suggested that many participants were interested in more training on AB and more scenario-based training specifically. Future iterations of the training should ensure that participants have sufficient time to practice intervention skills in a controlled setting. AB training should also be integrated with other trainings that are part of routine academy or in-service training. For example, use of force, de-escalation, and procedural justice training are opportunities to reinforce key concepts associated with AB.